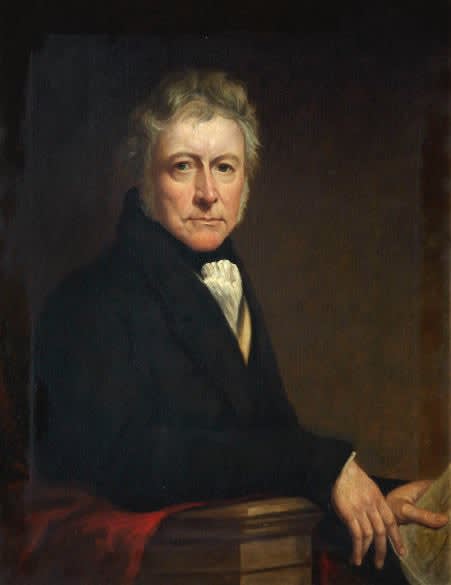

Ironically the name of William John Thomson RSA is not included in the pioneering Scottish Painters at Home and Abroad 1700-1900 written by David and Francina Irwin and published in 1975, despite having featured in the three standard books previously devoted to Scottish Art by Brydall (1889), McKay (1906) and Cursiter (1949).[1]

His name is worthy of mention as the first person born outwith the British Isles to be elected a full Royal Scottish Academician.

The son of a Scot, Alexander Thomson and his Georgian born bride Mary Elizabeth Spencer, Thomson was born on 3 October 1771 at Savannah in Georgia, then a British colony [since 1788 United States of America]. Following the birth of Thomson’s two sisters and with theAmerican War of Independence raging, Alexander evacuated his young family to Great Britain in 1776.[2]

Most references suggest they travelled to London where the young Thomson began painting portrait miniatures. He was certainly resident there by 1796 when he first exhibited at the Royal Academy. But by 1797 he was in Edinburgh where he married Helen Colhoun [sic] in Tron Parish on 12 May and where in 1798 the couple’s first child was born.

They then moved to London where a second son was born in 1799. There, Thomson is recorded at three different addresses on Piccadilly before moving to The Strand. He exhibited at the Royal Academy as well as at other of the major London exhibitions including the British Institution, The Old Watercolour Society and the [British] Associated Artists to which body he was elected a member on 29 July 1807. His exhibits were virtually all portraits, his preference being miniatures, but he also worked as a silhouettist. On 21 January 1808 years he was enrolled as a painting student at the Royal Academy Schools.[3]

In 1812 he returned to Edinburgh, possibly due to the death of his wife as he had remarried by the time his fourth child was born in that city in 1813. Edinburgh remained his home until his death there on 24 March 1845.

In Edinburgh he continued to exhibit with the [Scottish] Associated Artists in their annual exhibitions which he had previously done from his London address, as well as sending work south to the London exhibitions.

Outwith his art he served as a Director of the Caledonian Insurance Company during the early 1830s where a fellow Director was Henry Raeburn, son of the famous painter. [4]

Thomson was also a Member of the Celtic Society and was amongst its members who attended the society’s Fancy Ball in the Assembly Rooms on 29 January 1836 'dressed in full highland costume and handsomely equipped.'[5]

The move to Edinburgh saw Thomson’s repertoire broaden with works illustrative of literature, from Cervantes to James Thomson to Allan Ramsay, and later still turning to the Bible. Genre figurative works also featured more prominently amongst his exhibits and for the last four years of his life it was landscape that appears to have occupied him most. The change in subject matter also saw Thomson move increasingly to oil paint from the watercolours he had favoured earlier in his career.

This change was first detected in a review of his exhibit ‘A Visitation of Consolation to the Sick’ at the British Institution annual exhibition in 1828 stating that Thomson promised 'to be very useful in oil painting' and praising his taste and power of expression, but urging him to show 'greater clearness in his colouring.'[6]

Thomson reputedly declined the honour of a knighthood and in 1823 on the death of Sir Henry Raeburn Thomson’s younger brother lobbied Robert Dundas to have him appointed Raeburn’s successor as His Majesty’s Limner in Ordinary in Scotland[7]. The move was unsuccessful, and the position was given to David Wilkie.

Thomson was elected an Associate Member of the Institution for the Encouragement of the Fine Arts in Scotland on 17 April 1824 alongside William Allan, Alexander Nasmyth, William Nicholson, George Watson, John Watson, Hugh William Williams, Andrew Wilson, Samuel Joseph and William Henry Playfair.[8] They were soon to discover however that the creation of the title of “Associate” brought with it no practical benefit; artists were denied seats on the committee and had no voting powers.

Within a year a rift between the Directors and the artists had widened with some threatening to break away and form a new body; a move opposed by Thomson in a considered letter that urged restraint. Finally in 1826 a number broke away to establish the Scottish Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. The situation not having improved for those artists (including Thomson) who had remained loyal to the Institution, they too finally left in 1829 and joined the fledgling Academy. Thomson entered as one of the new full Academicians under the Hope-Cockburn settlement.

During all this time, Thomson appears to have made ends meet through private patronage and possible inheritance. A prolific creator and exhibitor, at his death Thomson enjoyed a reputation as one of the country’s leading artists. Since then, his name and his work has slipped largely and unfairly into obscurity, possibly because large parts of his career including knowledge of where and under whom he gained his initial training remain unresolved. That is something we are pleased to resolve in part in this exhibition.

- Robin Rodger, Documentation Officer

[1] Thomson also appears in Bryan’s Dictionary of Painters and Engravers (first pub 1816) but not in Allan Cunningham’s The Lives of the Most Eminent British Painters, Sculptors and Architects (1854) nor in Samuel Redgrave’s Dictionary of Artists of the English School (1874)

[2] https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~battle/genealogy/spencer.pdf

[3] e-mail correspondence RSA-Mark Pomeroy, Archivist, RA, October 2024 both confirming these details and refuting published references that his name was put forward for election to Associate rank of the RA at the same year.

[4] public notices in contemporary newspapers 1833-35, accessed via the British Newspaper Archive. Sir Henry Raeburn RA died in 1823 and it was his eldest son of the same name who served as a fellow Director.

[5] Inverness Courier, 3 February 1836, accessed via the British Newspaper Archive.

[6] London Courier and Evening Gazette, 18 February 1828, accessed via the British Newspaper Archive.

[7] NAS GD51/6/2195 (Dundas family Papers)

[8] Caledonian Mercury, 19 April 1824, accessed via the British Newspaper Archive.