2023 marks a double anniversary year of the life of Scottish painter Sir William Gillies RSA (1898-1973), who for various reasons – artistic, cultural, and political – has not been recognised in the story of British modernism in the way he truly deserves. Since Vasari’s The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, the fascination with stories of artists and their place in art has endured, but as with this seminal text, past interpretations can mislead and create impressions that do not reveal everything that could or should be revealed.

William Gillies, Self Portrait, oil on canvas, 1940. National Galleries Scotland (Purchased, 1979)

Of course, new research can provide answers. Perhaps Gillies was aware of this when he bequeathed his entire estate to the Royal Scottish Academy, where its presence in the RSA collections has fostered a deeper understanding of his life and artistic practice. In 1998, on the centenary of Gillies’ birth, an RSA exhibition and publication set out his stall as a major twentieth century British painter. Twenty-five years on, a new book supported by the RSA promises to change the way Gillies’ art has been understood, placing him firmly within the story of British modernism.

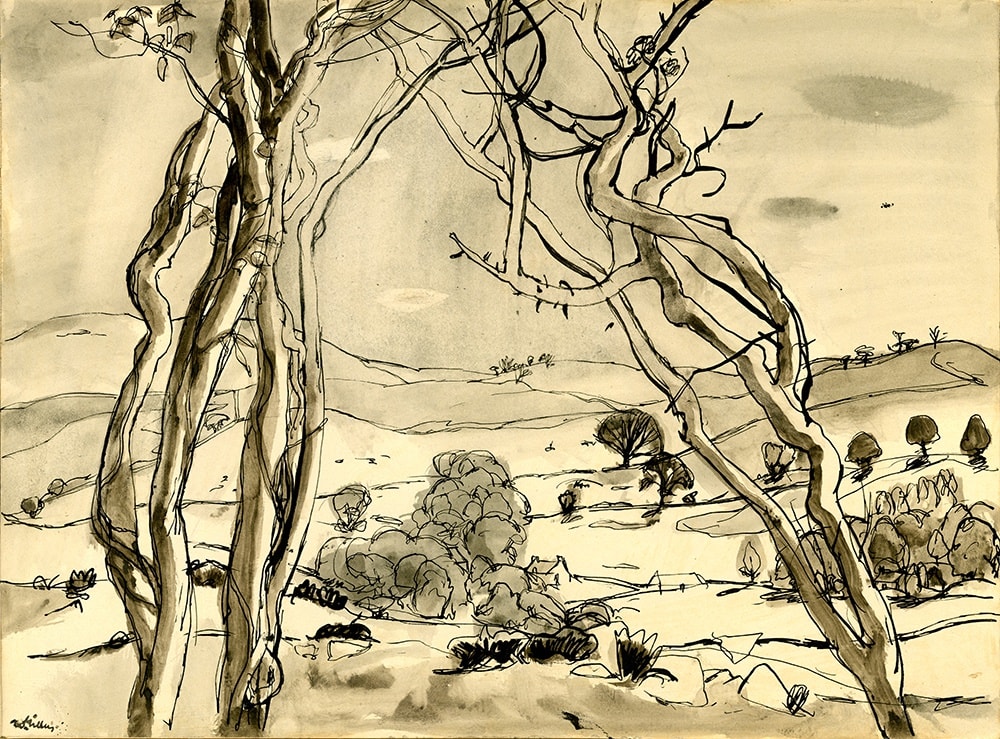

Solway Landscape, ink and wash, around 1953. RSA (Gifted from the estates of Nancie Barnes and Sylvia Hyde, 2013)

Before and soon after his death, there was a received view of Gillies as a countryman, who painted lyrical landscapes and only produced his best work when he abandoned the modernist distractions of his early years. Gillies preferred to involve himself in the practice of painting rather than any lofty interpretations and so did nothing to challenge this view. To him, his paintings did the talking, but in reinterpreting his life and art one can find dialogues that have until now been lying in the shadows.

Near Durisdeer, oil on canvas, around 1932-33. National Galleries Scotland (Bequeathed by Dr R. A. Lillie 1977)

Near Durisdeer, oil on canvas, around 1932-33. National Galleries Scotland (Bequeathed by Dr R. A. Lillie 1977)

Gillies was a wonderfully versatile artist, but one might think most of subtly complex still lifes, expressive landscapes in oil, and watercolours deftly balanced with ink line and wash. Bound together in all of these are a consummate understanding of colour and tone and a particularly strong bond to the Scotland in which he grew up, travelled, and settled as a mature artist. But there is so much more to Gillies than meets the eye.

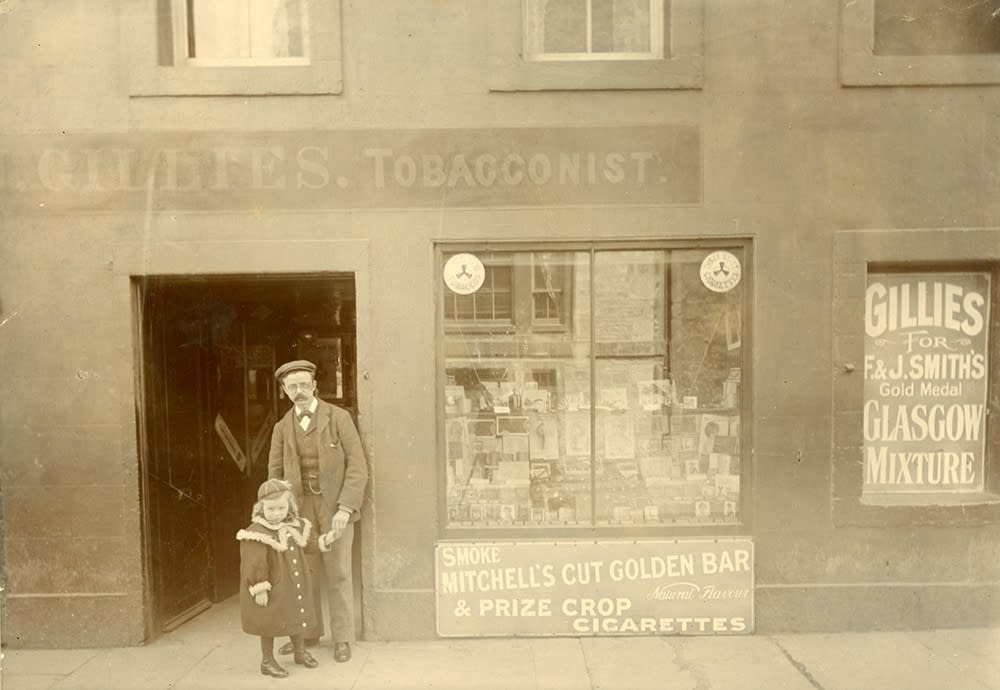

Gillies' father John and elder sister Janet outside the family business in Haddington, c.1899, photograph. RSA (Sir WIlliam Gillies Bequest, 1973)

Gillies was born and grew up in Haddington, a bustling market town in East Lothian, near the outskirts of Edinburgh. The town formed an interesting early influence as a place where country traditions and industrial modernity met. As a young artist Gillies excelled in drawing and painting, before being conscripted to the Western Front in 1917. This existential shock was among many – which began in his childhood and lasted for his first fifty years – that impacted his creative output and shaped the development of his painting.

Our Post Behind Our Wire, ‘meant to be Lawton and yours truly’, pencil, 1918. RSA (Sir William Gillies Bequest, 1973)

Gillies had begun his studies at Edinburgh College of Art in 1916 and returned in 1919 after being discharged from army service. The following summer of 1920 marked the first of some twenty-five summers which he spent touring around Scotland on painting trips with friends, which form the supremely well-travelled character of his landscape paintings over his career. The diversity of painterly approaches in these landscapes is nothing short of remarkable and this eclecticism may be partly to blame for his slipping detection as a painter of modernist concerns.

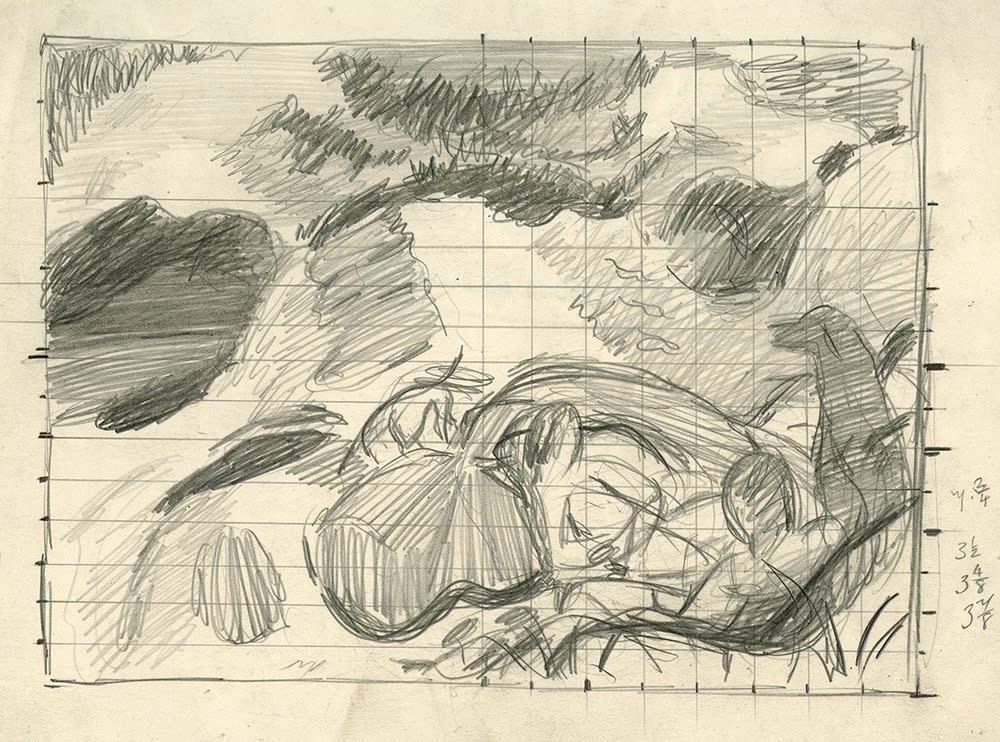

Picnic on the Beach, Morar I, pencil, around 1932. RSA (Sir William Gillies Bequest, 1973)

Picnic on the Beach, Morar ll, pencil, around 1932. RSA (Sir William Gillies Bequest, 1973)

Rocks and Water, Morar, oil on canvas, around 1932-34. RSA (Sir William Gillies Bequest, 1973)

Gillies was equally at home with an energetic and expressionistic application of paint as he was in a considered and careful cubist massing of forms, and never let one mode of thinking or approach dominate his painting for too long. In the film Still Life with Honesty (1970), he proclaimed “I believe I am now achieving a simplicity I have striven for, for a long long time, but nothing is static and I am free, in fact I am apt, to change direction without notice. But this is part of the fascination of the job of painting.”

Bathers, oil on canvas, around 1924. RSA (Sir William Gillies Bequest, 1973)

The first major change of direction in Gillies’ painting came after he spent time in the studio of Andre Lhote with his friend William Crozier in 1923-24. One would argue that Crozier’s art was more deeply influenced by Lhote’s methods, but it certainly opened Gillies’ eyes to new possibilities and paintings like Bathers, Florence and Trees on the Tyne, Haddington, among others, show how he absorbed the ideas and directed them into his own painterly style.

Still Life with Chagall Print, oil on canvas, 1933. RSA (Sir William Gillies Bequest, 1973)

In 1931, another major influence grew from the arrival in Edinburgh of a group of works by Edvard Munch which Gillies helped to secure directly from Oslo. Exhibited at the Scottish Society of Artists (SSA) Annual Exhibition, Munch showed Gillies that he could paint better by painting his own life and from here he began to open his work to his own traumas of family and war, as the threat of war began to grow again in the 1930s.

Still Life with Black Jug, oil on canvas, 1933. RSA (Sir William Gillies Bequest, 1973)

Works like Still Life with Chagall Print acknowledge this in subject and imagery, while paintings like Still Life with Black Jug and Poppies in a Yellow Vase play with, respectively, memorialisation (the black jug first appeared after the death of his friend William Crozier) and the presence of the artist in questioning his own interpretation of what is real. Works like his RSA Diploma painting Still Life, Yellow Jug and Striped Cloth took this questioning of planes of reality to its zenith later in his career.

Still Life, Yellow Jug and Striped Cloth, oil on canvas, around 1955. RSA (Diploma Collection Deposit, 1956)

Another SSA exhibition in 1934 brought into being Gillies’ curiosity in exploring the boundaries of figuration and abstraction in his painting. A display of twenty-five of Paul Klee’s paintings delighted Gillies and he and his friend John Maxwell painted half a dozen works in response. These included In Arniston and Harbour, but the interest in Klee and exploring the instabilities of meaning through colour and form had its origins a few years before, as works like Rocks and Water, Morar and Skye Hills from Morar evidence. Indeed, it is in this phase of 1930s creative experimentation that Gillies’ produced arguably his best watercolours, including Achgarve, Wester Ross, In Ardnamurchan and West Coast Sunset.

Skye Hills from [near] Morar, watercolour, around 1931. National Galleries Scotland (Bequeathed by Dr R. A. Lillie 1977)

Laide Looking Towards Ben More or Wester Ross, watercolour, around 1934 or 1937. Courtesy of the Blackadder Houston Trust

Key to Gillies’ outlet for experimentation in the 1930s was his membership of The Society of Eight and the regular exhibiting opportunities it presented. He was nominated to the Society by Samuel J Peploe and F C B Cadell and it enabled him to show daring paintings, which challenged accepted norms. In 1935, alongside Harbour, he exhibited a group of paintings he described as abstracts. Two of these paintings survive that show how far he took abstraction: Ascending and Untitled (most likely the painting titled Balanced from the exhibition). Although purely non-figurative abstraction did not endure in Gillies’ work, these paintings are important in understanding his thinking around perception and its various balances or imbalances.

Ascending, oil on canvas, 1936. RSA (Sir William Gillies Bequest, 1973)

Untitled or Balanced, oil on canvas, around 1935. RSA (Sir William Gillies Bequest, 1973)

Throughout Gillies’ life there was rarely a period where he was not rocked by the death or illness of close friends or family, and in 1936 this was most felt on the death of his younger sister Emma. She had shown early promise in ceramics and Gillies had been particularly close to her. Emma’s ceramics appear regularly in his still life paintings in a kind of object-based portraiture. Examples of figurative portraiture are rare in Gillies’ practice, but two years after Emma’s death his most ambitious work was portrait based. In Interior, Gillies appears with his mother and surviving sister Janet in an amazingly complex painting that plays with subjective and objective worlds through the mirror of the artist. In this way it is a homage to Velazquez, and from a painterly perspective to Bonnard, but it is much more than this and perhaps more than any other work, shows the intense intelligence of Gillies and how it manifested itself in his painting.

Interior, oil on canvas, 1938. RSA (Sir William Gillies Bequest, 1973)

The year after Interior, came Gillies’ move to Temple, a small village in Midlothian south of Edinburgh in the shadow of the Moorfoot Hills. Previous accounts have told this as the artist returning to his country roots, to get closer to the landscape that simply inspired him. However, the fact he uprooted himself and his family from Edinburgh as soon as war was declared in 1939 tells a different story connected to the existential crises of his life.

Interior of Studio, Temple, oil on canvas, around 1965. Private Collection.

In his later years the move to Temple brought with it the merging of still life and landscape as Gillies expertly weaved the interior of the cottage to surroundings outside its windows, bringing internal and external worlds together under one canvas. In watercolour he also experimented with still life to great effect in paintings such as Still Life with Blue Gloves and Still Life with Colour-Box. As a mature artist, nothing was out of reach for Gillies, but it remained bound up in his own search for signifiers in the human condition and an impulse to look forward as well as back.

Still Life with Colour-box, watercolour and pencil, 1967. RSA (Mrs Anne S Robertson Bequest, 2015)

The cascade of post-war watercolour landscapes are perhaps what Gillies has become best known for. However, a more accurate picture of the artist is formed by considering his oils in landscape and still life, his drawing and his watercolours together within the story of his life and the outlet of painting as a creative means to relieving its psychological stresses. In addition to the key moments of influence drawn from Klee, Munch and Lhote, over the years Gillies took inspiration from the abstractions of Kandinsky and Delaunay and notably from French art and painters such as Braque, Gauguin, Bonnard, Derain and Matisse. Closer to home, he found affinity with the likes of Paul Nash and Graham Sutherland, but Gillies’ pictorial intelligence meant he weaved and perfected myriad approaches in his own search for meaning and form in his painting.

Near Howgate, watercolour, 1951. NGS (Bequeathed by Dr R. A. Lillie 1977)

In his lifetime, Gillies’ stature as an artist was finally recognised outside of Scotland when he was made a Royal Academician in 1971. Outside his lifetime William Gillies: Modernism and Nation in British Art finally recognises his true stature and how he should be reinterpreted alongside the great British modernist painters of the twentieth century.

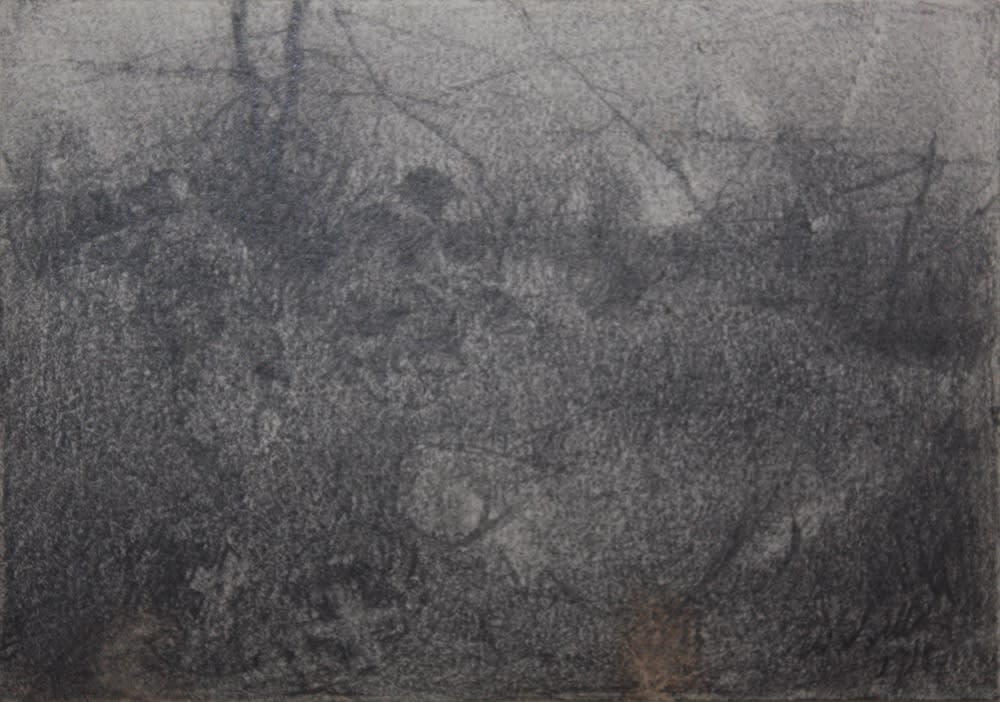

Plant Stems ll, pencil, around 1931-40. Royal Scottish Academy (Sir William Gillies Bequest, 1973)

William Gillies: Modernism and Nation in British Art by Andrew McPherson will be published by Edinburgh University Press, supported by the RSA, in October 2023. The book will be launched at the RSA exhibition William Gillies: Modernism and Nation, 9th December 2023 to 27th January 2024, Which will then tour around Scotland until 2026.