Each month, we’re sitting down with an artist to discuss their practice, influences and upcoming projects. Today, we’re speaking to Jo Ganter RSA about music, working in series and John Kinross Scholarships.

After graduating from Edinburgh College of Art, you were awarded an RSA John Kinross Scholarship. How did the time you spent in Florence and Italy influence your practice? And do you have any words of wisdom for the list of twelve artists and architects who have been awarded scholarships in 2024?

I remember posting my application into the back door of the RSA in 1988 and crossing my fingers. It was difficult to write an application to travel to somewhere as beautiful as Tuscany and sound different and genuine (I mean, why wouldn’t you want to go there?!). In the end, I wrote that I wanted to live there long enough for this very beautiful place to become ordinary, so that I could see it as a resident rather than a tourist. It was the first thing I ever won. I advise all my students to apply for it now. It’s a fantastic opportunity. Advice: learn Italian and you will be welcomed and helped in that country. I went to Florence in July. Advice: wait for a cooler month if possible. However, it meant I could rent a room in a student flat while they were on summer vacation. It also meant I made friends with some of those students which was a huge bonus. They wrapped their dining table in brown paper so I could work on it and make as much mess with charcoal and paint as I wanted. They drove me to interesting places and to the huge supermarkets on the edge of town to buy bottles of water cheaply. They also acquired as many mosquito repellents as they could for me! I loved the architecture, the narrow streets opening into squares, and the dramatic light and shadow these created. The etching I made of one of the markets was chosen for the RSA collection. I’d forgotten all about it until it was shown at the Italian consulate recently.

The John Kinross Scholarship was important to me artistically because of the new environment it allowed me to absorb, and because it gave me a self-belief that I could apply for opportunities and be successful. The next year I was awarded a Rome Scholarship which gave me nine, very productive and happy months, at the British School at Rome, alongside other artists. It was a special year.

Your work is often collaborative, involving musicians to create graphic scores and using sound as inspiration for abstract composition. Is there a particular musician you find yourself drawn to for your studio soundtrack?

The images tend to come first, and then the music. The music doesn’t inspire the images as such, but shapes, tones, and colours, become associated with different kinds of musical material, instrumentation, pitch and tone.

Until 2014, I’d never thought to work collaboratively, ut I was friends with musicians and have a love for music. When Edinburgh College of Art became part of the University of Edinburgh, Raymond MacDonald, who I’d known for many years, became Head of Music and a colleague. He wanted to create images to direct music: graphic scores. I thought that original prints would be ideal as a way of putting individual artworks onto every musician’s music stand. We collaborated on the images and the musical instruction to make this happen for our first exhibition at the Talbot Rice Gallery in 2015, Running Under Bridges.

Running Under Bridges

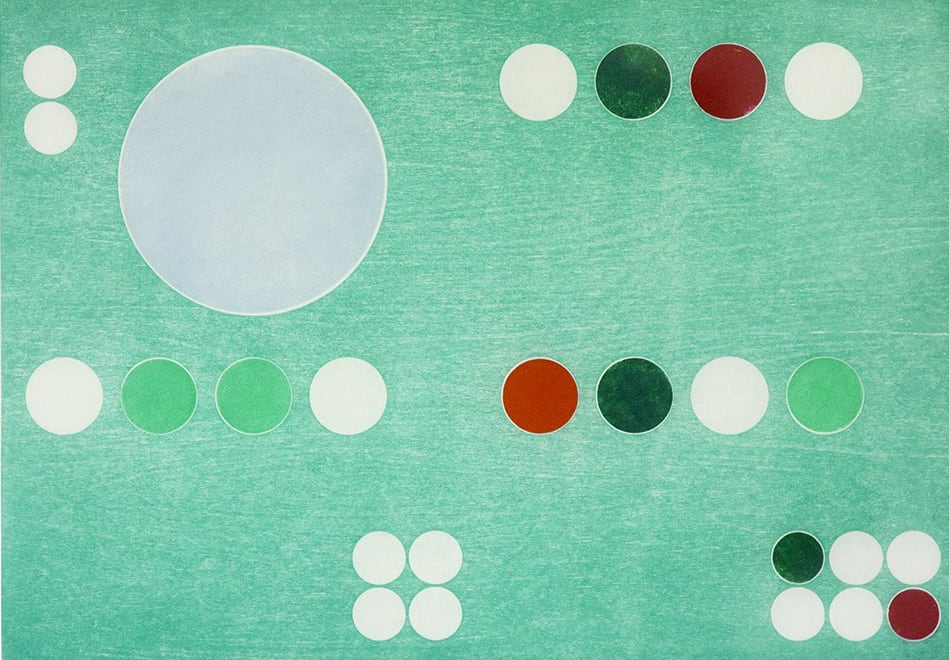

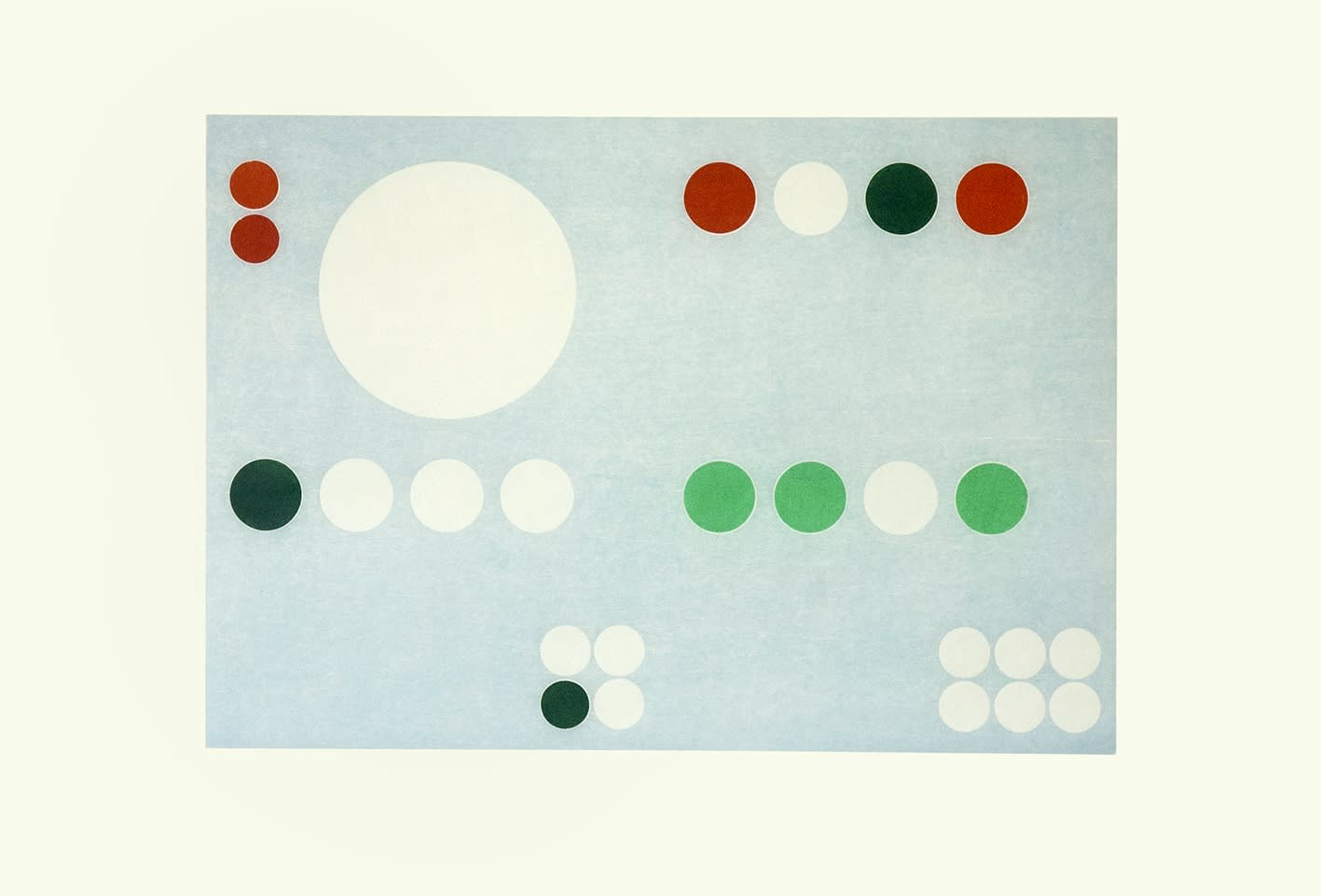

Silent Music | Seeing Sound was shown at the RSA in 2019. Silent Music and Seeing Sound are relief prints, printed from wooden blocks that have been laser cut to give perfect circles. The circles were removed from the rectangular template to be inked in a variety of colours and returned to the template after it had been inked. The musicians were told to read the score conventionally, from top left to bottom right. The colours indicate which musician should play when, and the tone of the colour suggests the tone or pitch of the music. Blank circles retain the colour of the paper and indicate silent pauses. One musician played the overall texture suggested by the woodgrain of the template. The composition of the music, represented visually this way, is evident at one glance while giving specific direction to the musicians playing it. The musicians have freedom to improvise while following the directions indicated in the score.

Seeing Sound

The wonderful thing about collaboration is that you can meet and work with many musicians. Raymond introduced me to American jazz pianist, Marilyn Crispell. I worked with her to create a suite of graphic scores, Gradations of Light, and Marilyn invited David Rothenberg, to play them with her. David works with electronic recordings of the natural world, from birds to bugs. I invited him to make a soundtrack for my film, Urgent Nature, which was shown at GoMA as part of Drink in the Beauty, an exhibition which showcased female artists working with the natural environment.

Each musician takes my work in a different direction. The work I make with Raymond MacDonald is fundamentally abstract and for any musician to play. They are geometric and brightly coloured. The suite I made with Marilyn Crispell are similarly geometric but made in response to the woodlands around her home in Woodstock, NY. Although abstract, they are monochromatic and for her to play. Urgent Nature is based on a series of documentary photographs I took in Scotland along the River Carron. My interpretation of them was based both on the matrices I was drawing for work with Marilyn and Raymond, but also the sounds that David records and produces as he plays with birds and other, industrial, sounds that intrude on his own world along the River Hudson. I wanted to express that constant human presence in the reclaimed industrial landscape I was documenting; David’s sound was perfect.

Ten years after starting to collaborate with Raymond MacDonald on what I thought would be a short project, I realise that music has been the driving force for my work ever since.

What is your most memorable experience or achievement throughout your career to date?

New York has provided my most memorable experiences. I first went there in 1994 with the help of a Boise Scholarship which enabled me to work in different print workshops in America for six months. I wrote to Robert Blackburn at his workshop in New York to ask if I could base myself there, no emails then! He replied that I could, and I packed a rucksack and arrived in June. Bob Blackburn was an African American printmaker who received a MacArthur lifetime achievement award for his contribution to art and promotion of African American rights. His workshop was a truly generous and collaborative space for people of all races and levels of expertise to work and share their skills. He was amazingly generous to me. You could pay to work just mornings or just afternoons. I think I chose mornings, so I’d have time to see New York and because it was cheaper than working all day, but Bob demanded to know why I wasn’t working all day and made it clear that I could, for free. He also phoned curators, announced to them that he had ‘this amazing artist from Scotland’ they must meet, and promptly handed me the phone. I was very shy, and it could have been awkward, but the people on the phone were accustomed to Bob’s introductions and invited me to show them work. I met Roberta Waddell, curator of prints at NY Public Library that way and the collection acquired the suite of lithographs I made in America. I was an etcher, but Bob was a lithographer, so I learned more about stone lithography in his workshop and continued making lithographs at the KALA Art Institute in California, my next stop on my American tour of workshops.

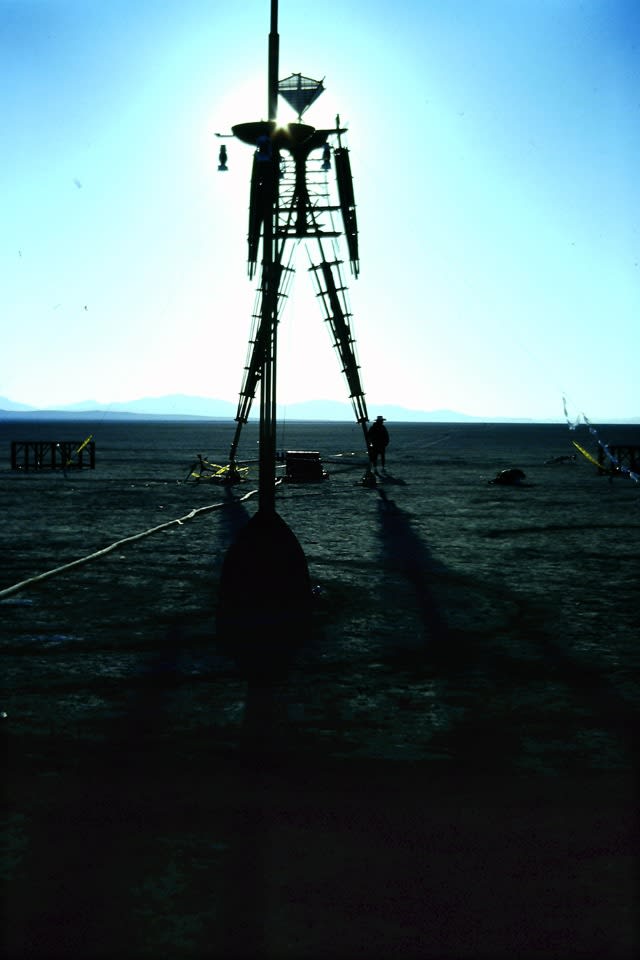

KALA was equally wonderful. Huge, the original Heinz Ketchup factory, 24-hour access, and home to the largest etching presses I’d ever seen. They gave me three months scholarship to make prints there. I found a house with two people advertising a room and they took me to The Burning Man Festival - that’s memorable!

Burning Man

After that trip, I went back several times, once, helped by The Scottish Arts Council, to work at Dieu Donné, a papermill that works exclusively with artists to make work with paperpulp. I began work there the second time on Monday 10 September 2001, Tuesday was 9/11. I’d been wandering around lower Manhattan waiting for Pearl Paint to open at 9am. There were a few sirens I thought nothing of, it was New York. Just before 9 I joined the queue outside Pearl Paint and the staff in the store told us that two planes had gone into the World Trade Towers. Everyone continued their business in a daze. I went to the fifth floor to get masking tape, (I was going to make grid-shaped watermarks in the paper pulp). The fire door was opened and framed in it, the top of the towers with perhaps three-storey high holes ripped through them, white then red at the edges, like cigarette ash when it’s been left to burn for too long. It was shocking but it didn’t cross my mind that the towers would fall. The staff at Dieu Donné were amazing and reopened the next day to work with me. I made the work I planned to make. Abstract pieces in overbeaten linen pulp that would dry to be translucent. Watermarks of grids, black and grey squares hovering, and fragile lines drawn onto the deckle with pulp pushed through a syringe. In my mind they’ll always be associated with 9/11.

You tend to work in series, with each work engaging in quite different pictorial ideas but always strongly attached to grid-like composition. Do you find this method of working aligns best with a certain medium?

It seems logical to work in series because no one image can say everything. I need to evolve ideas visually from one work to another. When I’m in a series, I think I’ll be involved with it forever. But at a certain point, I always realise that it’s over and I need to struggle again for a new idea. I think that working in series also allows the spectator to engage with ideas better.

Drawing and painting are natural and accessible media to use. I think using pens, pencils, and paint, then translate my ideas into etching or relief printing. Printmaking provides a resistance to the artist. You must work out how to translate images to multiple plates or blocks. ‘Slight’ marks, made incidentally while drawing, even accidentally, need to be assessed for their importance when scaling the image up to print: are they important? Most often these are the nuances in an image that are most important. My present medium of relief printing embraces this kind of enquiry, being one of the most resistant methods of making, and I enjoy it for that.

Jo Ganter RSA, Photo Julie Howden

You were elected as Treasurer of the RSA last June, and currently sit on Standing Committee. Is there anything new or unexpected your current role has taught you about the Academy?

I’ve previously been part of a number panels to select artworks and help hang exhibitions in the Academy. These are all roles that seem natural for an artist to fulfil - looking at and art and being interested in other artists’ work. As Treasurer, I have to look at the money, and that feels more like hard work! But, as part of the Standing Committee, I’m privileged to see the whole of the Academy and I’m proud of how many artists we support through the awards and residencies we enable, the exhibitions we curate, and the amazing collection we care for and make accessible. I’m pleased that the Academy, while supporting its Academicians, isn’t only for Academicians. It’s for all artists in Scotland and everyone interested in art.

And finally, as we look forward to our 200th anniversary in 2026, what are you most excited about?

Everything! But mostly, the outreach programme we’re curating with institutions all over Scotland to highlight the work of Academicians held in their collections. It’s important the Academy has a reach beyond Princes Street, and this will really emphasise our national role.

Explore Jo Ganter RSA's work further