-

Benno Schotz RSA, The Generations (detail)

Benno Schotz RSA, The Generations (detail) -

Fanindra Bose ARSA, The Hunter (detail). Courtsey of the National Museum of Wales.

Fanindra Bose ARSA, The Hunter (detail). Courtsey of the National Museum of Wales. -

Artists

-

-

-

-

Benno Schotz RSACherna at 7, 1937Bronze bust on wood plinth49.5 x 34 x 29 cm

Benno Schotz RSACherna at 7, 1937Bronze bust on wood plinth49.5 x 34 x 29 cm -

![Benno Schotz RSA Cherna as Nefertiti, 1981 Plaster [ochred] 52 H x 27.5 W x 29 D cm](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7) Benno Schotz RSACherna as Nefertiti, 1981Plaster [ochred]52 H x 27.5 W x 29 D cm

Benno Schotz RSACherna as Nefertiti, 1981Plaster [ochred]52 H x 27.5 W x 29 D cm -

Benno Schotz RSACherna as Nefertiti, 1981Bronze49.5 H x 38 W x 27.5 D cm

Benno Schotz RSACherna as Nefertiti, 1981Bronze49.5 H x 38 W x 27.5 D cm -

Benno Schotz RSAAmiel, the sculptor's son, 1979Plaster bust [ochred}40 H x 24 W x 28 D cm

Benno Schotz RSAAmiel, the sculptor's son, 1979Plaster bust [ochred}40 H x 24 W x 28 D cm

-

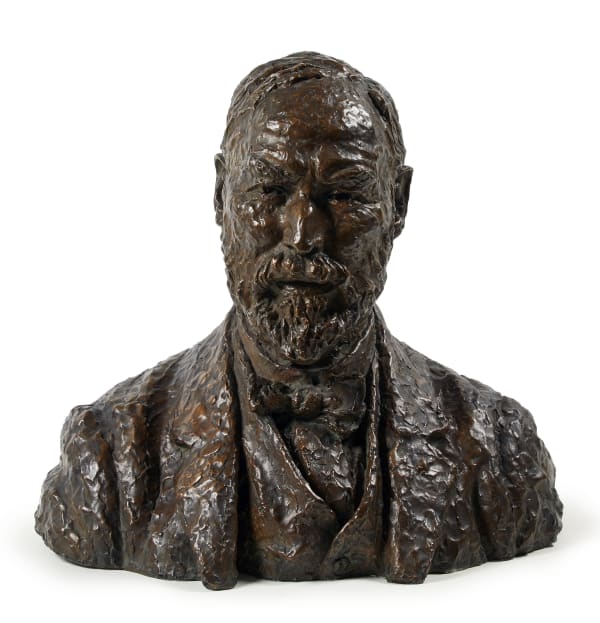

Benno Schotz RSASir William MacTaggart PPRSA, 1970Bronze66 H x 59 W x 34 D cm

Benno Schotz RSASir William MacTaggart PPRSA, 1970Bronze66 H x 59 W x 34 D cm -

Benno Schotz RSASir James Lewis Caw, 1864-1950, Art Historian and Curator, 1928Bronze45.5 H x 51 W x 30 D cm

Benno Schotz RSASir James Lewis Caw, 1864-1950, Art Historian and Curator, 1928Bronze45.5 H x 51 W x 30 D cm -

Benno Schotz RSAThe Generations, c. 1968Plaster36 H x 24.5 W x 20.5 D cm

Benno Schotz RSAThe Generations, c. 1968Plaster36 H x 24.5 W x 20.5 D cm -

![Benno Schotz RSA Figure Study Plastic metal [green patina] on wooden base 40.5 H x 16.5 W x 10 D cm](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7) Benno Schotz RSAFigure StudyPlastic metal [green patina] on wooden base40.5 H x 16.5 W x 10 D cm

Benno Schotz RSAFigure StudyPlastic metal [green patina] on wooden base40.5 H x 16.5 W x 10 D cm

-

Benno Schotz RSAVenus in the Park, c. 1961Terracotta48.5 H x 13 W x 14 D cm

Benno Schotz RSAVenus in the Park, c. 1961Terracotta48.5 H x 13 W x 14 D cm -

Benno Schotz RSAMale Torso, 1957Terracotta58 H x 56 W x 32 D cm

Benno Schotz RSAMale Torso, 1957Terracotta58 H x 56 W x 32 D cm -

Benno Schotz RSAThe Iron KnightTerracotta sprayed with iron58 x 28 x 18 cm

Benno Schotz RSAThe Iron KnightTerracotta sprayed with iron58 x 28 x 18 cm -

Benno Schotz RSAAlan Fletcher with Euphonium, 1957Terracotta106 H x 65.5 W x 49 D cm

Benno Schotz RSAAlan Fletcher with Euphonium, 1957Terracotta106 H x 65.5 W x 49 D cm

-

Benno Schotz RSAStations of the Cross, c. 1960-65Plasticine on hardboard22.8 x 161 cm

Benno Schotz RSAStations of the Cross, c. 1960-65Plasticine on hardboard22.8 x 161 cm -

Benno Schotz RSAUncle Manny, 1914Gilt painted plaster relief36.5 x 46.5 cm

Benno Schotz RSAUncle Manny, 1914Gilt painted plaster relief36.5 x 46.5 cm -

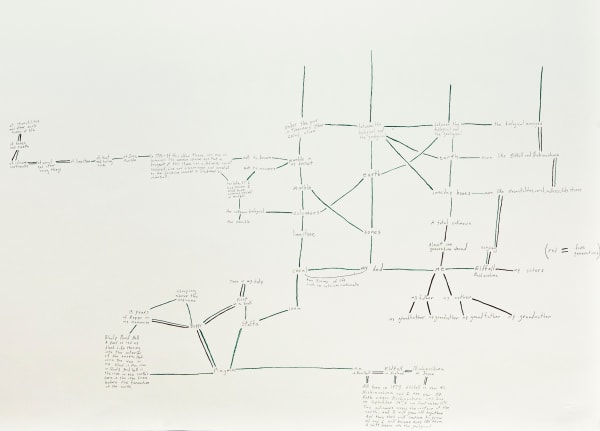

Benno Schotz RSAUntitled figurative abstraction sketch, around 1950 to 1980Pen and ink on paper29.6 x 41.7 cm

Benno Schotz RSAUntitled figurative abstraction sketch, around 1950 to 1980Pen and ink on paper29.6 x 41.7 cm -

Benno Schotz RSAUntitled tree abstraction sketch, around 1950 to 1980Pen and ink on paper25.3 x 18.8 cm

Benno Schotz RSAUntitled tree abstraction sketch, around 1950 to 1980Pen and ink on paper25.3 x 18.8 cm

-

-

Ade Adesina in his studio. Photo Sandy Wood.

Ade Adesina in his studio. Photo Sandy Wood. -

-

Fanindra Nath Bose

Fanindra Nath Bose -

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSA, The Sacrifice od Youth, bronze, form Ormiston War Memorial.

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSA, The Sacrifice od Youth, bronze, form Ormiston War Memorial. -

-

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSAThe Hunter, 1914Bronze50.2 x 23.3 x 21.6 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSAThe Hunter, 1914Bronze50.2 x 23.3 x 21.6 cm -

![Fanindra Nath Bose ARSA Male Bust [possibly Leslie Galloway], c. 1908-26 Bronze on a marble plinth 19.8 x 7.7 x 8 cm](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7) Fanindra Nath Bose ARSAMale Bust [possibly Leslie Galloway], c. 1908-26Bronze on a marble plinth19.8 x 7.7 x 8 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSAMale Bust [possibly Leslie Galloway], c. 1908-26Bronze on a marble plinth19.8 x 7.7 x 8 cm -

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of unidentified sculpture group of dead old man and nude boy with dagger, 1911Pencil on paper26.0 x 20.3 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of unidentified sculpture group of dead old man and nude boy with dagger, 1911Pencil on paper26.0 x 20.3 cm

-

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of stone bas relief Imperial France bringing light to the world and protecting Science, Agriculture and Industry, Pavillon de Flora, Louvre, Paris, 1911Pencil on paper27.6 x 21.5 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of stone bas relief Imperial France bringing light to the world and protecting Science, Agriculture and Industry, Pavillon de Flora, Louvre, Paris, 1911Pencil on paper27.6 x 21.5 cm

-

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of unidentified bas relief ox skull with swags of fruit, 1911Pencil on paper27.6 x 21.5 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of unidentified bas relief ox skull with swags of fruit, 1911Pencil on paper27.6 x 21.5 cm

-

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of Bacchanal plaster roundel by A-J Dalou, 1911Pencil on paper23.2 x 21 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of Bacchanal plaster roundel by A-J Dalou, 1911Pencil on paper23.2 x 21 cm -

![Fanindra Nath Bose ARSA Sketch of Le Baiser [The Kiss] by Auguste Rodin, 1911 Pencil on paper 25 x 17.6 cm](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7) Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of Le Baiser [The Kiss] by Auguste Rodin, 1911Pencil on paper25 x 17.6 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of Le Baiser [The Kiss] by Auguste Rodin, 1911Pencil on paper25 x 17.6 cm -

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of Age of Bronze, 1877, by Auguste Rodin, Paris, 1911Pencil on paper27.6 x 21.5 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of Age of Bronze, 1877, by Auguste Rodin, Paris, 1911Pencil on paper27.6 x 21.5 cm

-

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of Au But by Afred Boucher, 1886, Musee Camille Claudel, Nogent-sur-Seine, 1911Pencil on paper20.4 x 26.1 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of Au But by Afred Boucher, 1886, Musee Camille Claudel, Nogent-sur-Seine, 1911Pencil on paper20.4 x 26.1 cm

-

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSALife study of standing female nude with right leg raised, leaning on a chair, 1911Pencil on paper32.6 x 24.9 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSALife study of standing female nude with right leg raised, leaning on a chair, 1911Pencil on paper32.6 x 24.9 cm -

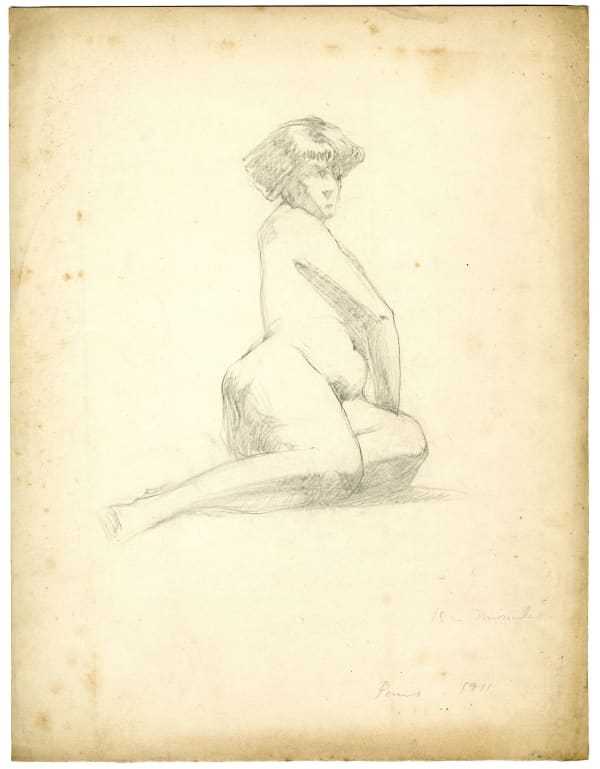

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSALife Study of a Seated Female Nude in Repose, 1911Pencil on paper32.2 x 24.8 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSALife Study of a Seated Female Nude in Repose, 1911Pencil on paper32.2 x 24.8 cm -

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of horse from basin of La Fontaine d'Observatoire, by Carpeaux, Jardin de Luxembourg, Paris, 1911Pencil on paper21.4 x 27.7 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of horse from basin of La Fontaine d'Observatoire, by Carpeaux, Jardin de Luxembourg, Paris, 1911Pencil on paper21.4 x 27.7 cm

-

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of horse from basin of La Fontine d'Observatoire, by Carpeaux, Jardin de Luxembourg, Paris, 1911Pencil on paper21.5 x 27.6 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of horse from basin of La Fontine d'Observatoire, by Carpeaux, Jardin de Luxembourg, Paris, 1911Pencil on paper21.5 x 27.6 cm

-

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of the bronze allegorical figures atop La Fontaine d'Observatoire, by Carpeaux, Jardin de Luxembourg, Paris, 1911Pencil on paper27.6 x 21.5 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of the bronze allegorical figures atop La Fontaine d'Observatoire, by Carpeaux, Jardin de Luxembourg, Paris, 1911Pencil on paper27.6 x 21.5 cm

-

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of the bronze allegorical figure of America atop La Fontaine d'Observatoire, by Carpeaux, Jardin de Luxembourg, Paris, 1911Pencil on paper27.8 x 21.6 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of the bronze allegorical figure of America atop La Fontaine d'Observatoire, by Carpeaux, Jardin de Luxembourg, Paris, 1911Pencil on paper27.8 x 21.6 cm

-

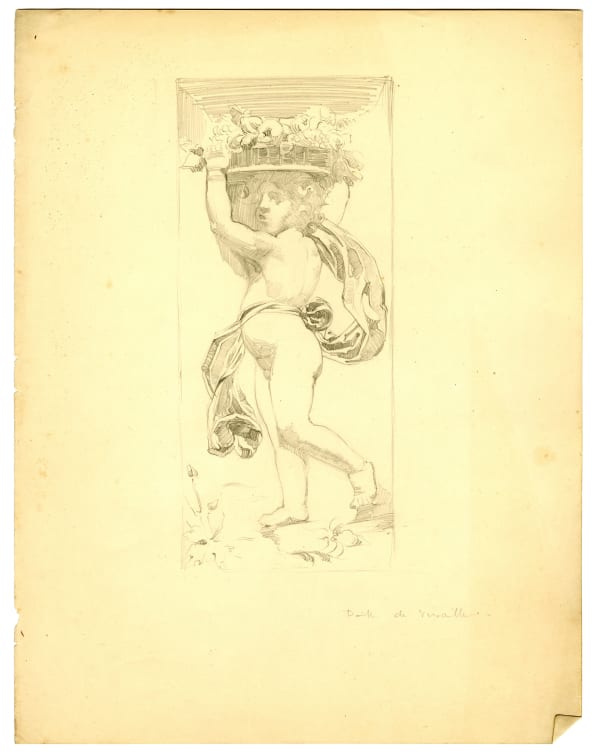

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of bronze bas relief of putti, Nicolas Legendre, Versailles, 1911Pencil on paper27.6 x 21.5 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of bronze bas relief of putti, Nicolas Legendre, Versailles, 1911Pencil on paper27.6 x 21.5 cm

-

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of bronze bas relief of putti, Etienne Le Hongre, Versailles, 1911Pencil on paper27.6 x 21.5 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of bronze bas relief of putti, Etienne Le Hongre, Versailles, 1911Pencil on paper27.6 x 21.5 cm -

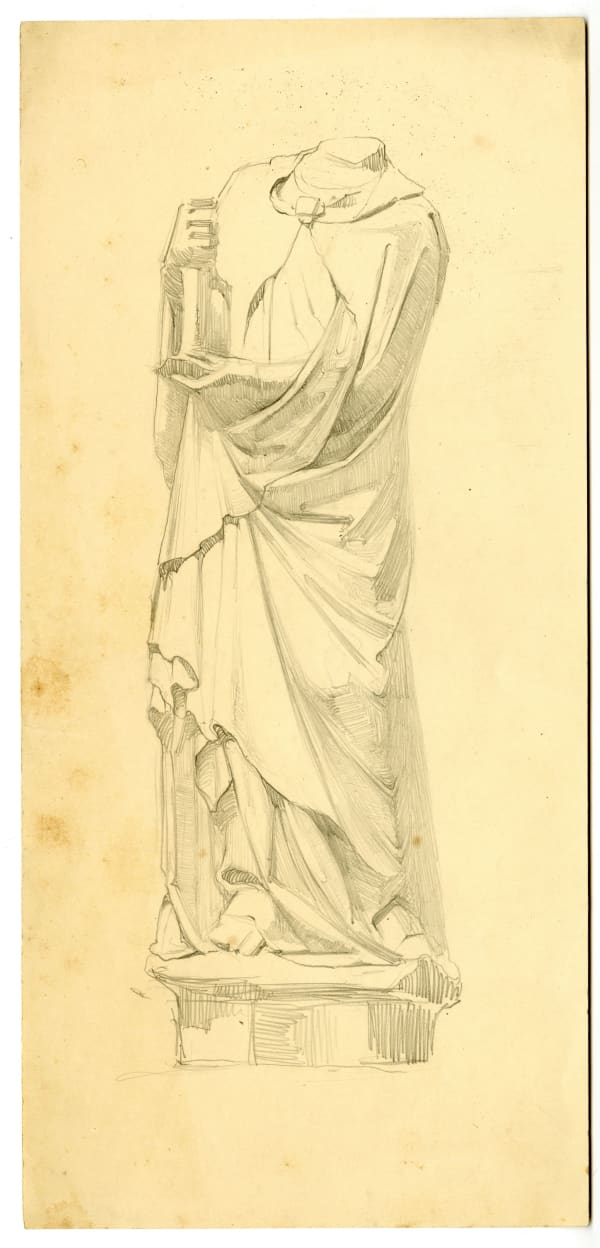

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of headless statue XIV at Eglise St Martin a Laon, 1911Pencil on paper26 x 12.1 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of headless statue XIV at Eglise St Martin a Laon, 1911Pencil on paper26 x 12.1 cm -

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of headless statue XIII at Eglise St Martin a Laon, 1911Pencil on paper26.1 x 12 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of headless statue XIII at Eglise St Martin a Laon, 1911Pencil on paper26.1 x 12 cm -

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of statue of Eve and the Serpent, Reims Cathedral, 1911Pencil on paper26 x 12.1 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of statue of Eve and the Serpent, Reims Cathedral, 1911Pencil on paper26 x 12.1 cm

-

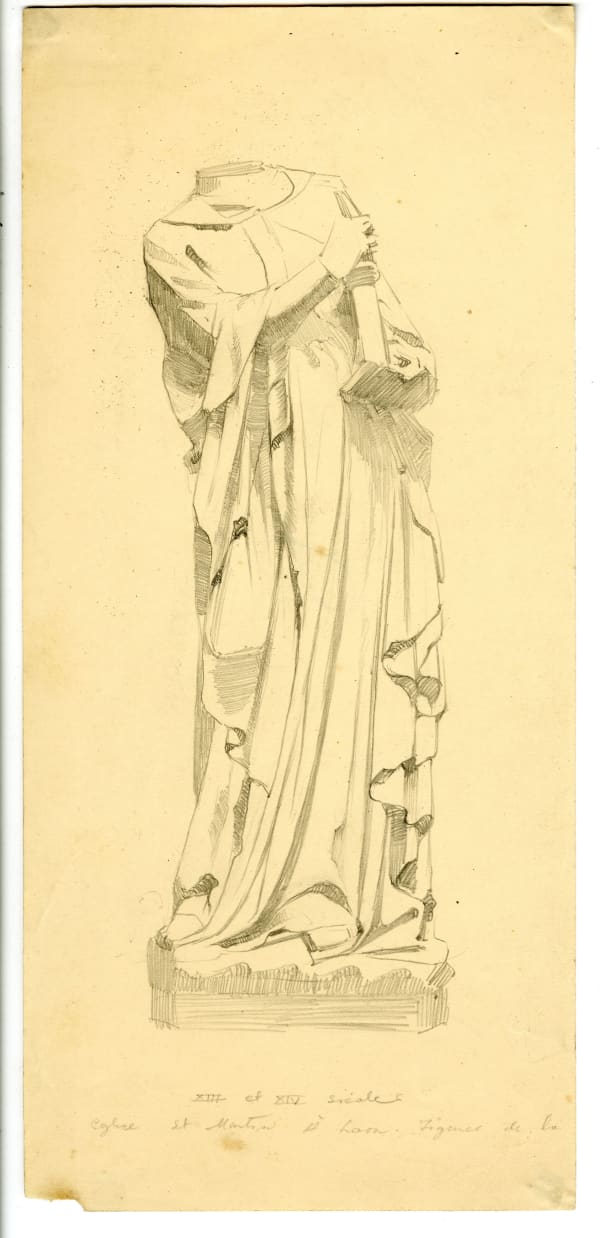

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of statue of standing Christ with book and hand raised in benediction, jamb of the central Portal of the Beau Dieu, West front of Amiens Cathedral, 1911Pencil on paper27.2 x 13.3 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of statue of standing Christ with book and hand raised in benediction, jamb of the central Portal of the Beau Dieu, West front of Amiens Cathedral, 1911Pencil on paper27.2 x 13.3 cm -

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of stone carving of St Firmin, Amiens Cathedral, 1911Pencil on paper26.1 x 12.2 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch of stone carving of St Firmin, Amiens Cathedral, 1911Pencil on paper26.1 x 12.2 cm -

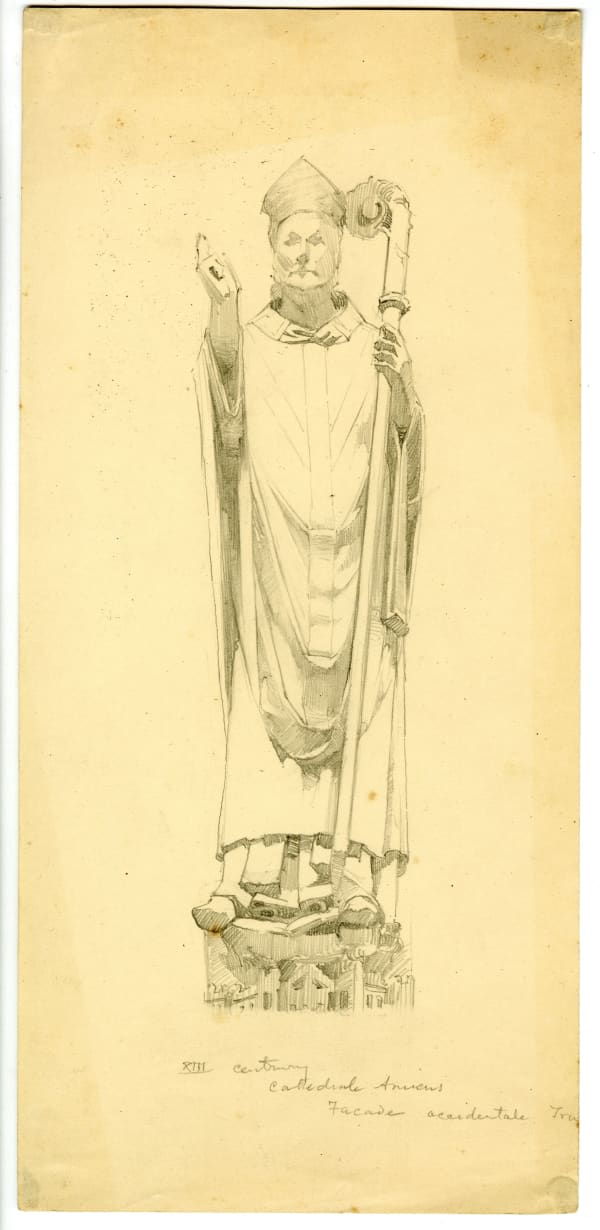

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch for sculpture possibly Bose's To The Well, 1911Pencil on paper26 x 20.3 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch for sculpture possibly Bose's To The Well, 1911Pencil on paper26 x 20.3 cm -

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch for sculpture possibly Bose's To The Well, 1911Pencil on paper26.1 x 20.4 cm

Fanindra Nath Bose ARSASketch for sculpture possibly Bose's To The Well, 1911Pencil on paper26.1 x 20.4 cm

-

-

Thomas Joshua Cooper in his studio.

Thomas Joshua Cooper in his studio. -

-

-

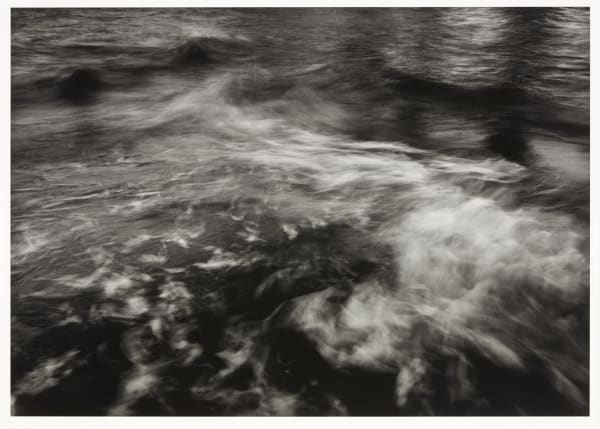

Thomas Joshua Cooper RSAMid morning - The source stream of the River Forth, Rising from Loch Chon. Near Inversnaid, Stirlingshire, Scotland, UK, Europe, 1997/2014Silver gelatin print, hand toned and printed by the artist41.5 x 59.4 cm

Thomas Joshua Cooper RSAMid morning - The source stream of the River Forth, Rising from Loch Chon. Near Inversnaid, Stirlingshire, Scotland, UK, Europe, 1997/2014Silver gelatin print, hand toned and printed by the artist41.5 x 59.4 cm -

Thomas Joshua Cooper RSAMid afternoon - The headwaters of the River Forth. Near Aberfoyle, Stirlingshire, Scotland, UK, Europe, 1997/2014Silver gelatin print, hand toned and printed by the artist41.5 x 59.4 cm

Thomas Joshua Cooper RSAMid afternoon - The headwaters of the River Forth. Near Aberfoyle, Stirlingshire, Scotland, UK, Europe, 1997/2014Silver gelatin print, hand toned and printed by the artist41.5 x 59.4 cm -

Thomas Joshua Cooper RSALate afternoon - The mouth of the River Forth, The Firth of Forth. South Queensferry, West Lothian, Scotland, UK, Europe, 1991/2014Silver gelatin print, hand toned and printed by the artist41.5 x 59.4 cm

Thomas Joshua Cooper RSALate afternoon - The mouth of the River Forth, The Firth of Forth. South Queensferry, West Lothian, Scotland, UK, Europe, 1991/2014Silver gelatin print, hand toned and printed by the artist41.5 x 59.4 cm -

Thomas Joshua Cooper RSAEvening - The mouth of the River Forth, The Firth of Forth. North Queensferry, Fife, Scotland, UK, Europe, 1991/2014Silver gelatin print, hand toned and printed by the artist41.5 x 59.4 cm

Thomas Joshua Cooper RSAEvening - The mouth of the River Forth, The Firth of Forth. North Queensferry, Fife, Scotland, UK, Europe, 1991/2014Silver gelatin print, hand toned and printed by the artist41.5 x 59.4 cm

-

-

Joe Fan in his studio

Joe Fan in his studio -

-

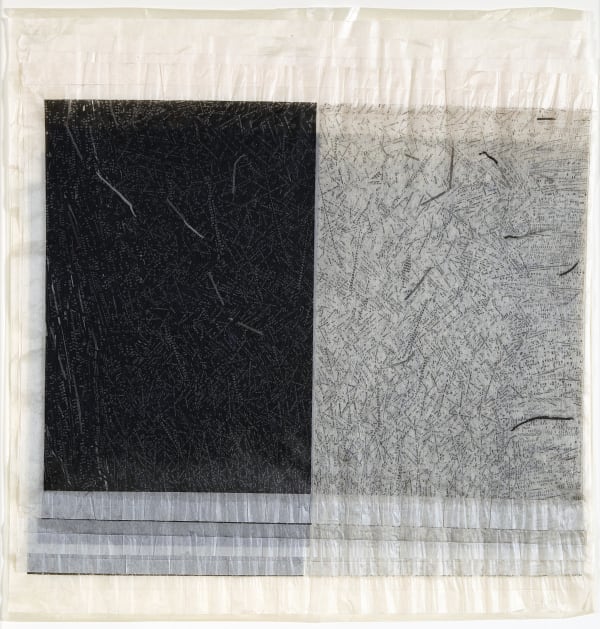

Beth Fisher, Anecdotal Plate 1

Beth Fisher, Anecdotal Plate 1 -

Beth Fisher's studio

Beth Fisher's studio -

Ilana Halperin. Photo Kulturhaus Villa Sträuli

Ilana Halperin. Photo Kulturhaus Villa Sträuli -

Work by Ilana Halperin.

Work by Ilana Halperin. -

-

Ilana Halperin RSAFrom Coral to Marble, 2014Hand polished Iona marble found by the artist during fieldwork on the island in 2014, coral gifted to the artist by keepers of a Natural History collectionVariable dimensions

Ilana Halperin RSAFrom Coral to Marble, 2014Hand polished Iona marble found by the artist during fieldwork on the island in 2014, coral gifted to the artist by keepers of a Natural History collectionVariable dimensions -

Ilana Halperin RSALearning to Read Rocks III, 2014Graphite on Fabriano paper81 x 112 cm

Ilana Halperin RSALearning to Read Rocks III, 2014Graphite on Fabriano paper81 x 112 cm

-

-

Unknown photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (Souce: NPG)

Unknown photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (Souce: NPG) -

![Otto Leyde (1835-1897), Prussia [now Russia]](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7) Otto Theodor Leyde

Otto Theodor Leyde -

Leena Nammari in her studio. Photo Norman McBeath RSA.

Leena Nammari in her studio. Photo Norman McBeath RSA. -

Leena Nammari RSA, …it can only be here… (detail)

Leena Nammari RSA, …it can only be here… (detail) -

Jacki Parry in her studio.

Jacki Parry in her studio. -

Jacki Parry's studio.

Jacki Parry's studio. -

William John Thomson RSA, Self-Portrait

William John Thomson RSA, Self-Portrait -

James Pittendrigh MacGillivray RSA (1856-1938), Portrait bust of Phoebe Traquair HRSA, c. 1895, plaster

James Pittendrigh MacGillivray RSA (1856-1938), Portrait bust of Phoebe Traquair HRSA, c. 1895, plaster -

Pheobe Anne Traquair, Head of a Girl

Pheobe Anne Traquair, Head of a Girl -

-

Phoebe Anna Traquair HRSAThe House of Life, 1903Enamel in silver mountOpen: 18.9 x 19 x 4 cm

Phoebe Anna Traquair HRSAThe House of Life, 1903Enamel in silver mountOpen: 18.9 x 19 x 4 cm -

Phoebe Anna Traquair HRSAThe Voyage, 1911enamel pendant in quatrefoil gold mount6.5cm x 4.2cm + 44.1cm (length of chain)

Phoebe Anna Traquair HRSAThe Voyage, 1911enamel pendant in quatrefoil gold mount6.5cm x 4.2cm + 44.1cm (length of chain) -

Phoebe Anna Traquair HRSAThe Annunciation to the Shepherds, 1900Enamel in copper mount6.5 x 9 x 6.1 cm

Phoebe Anna Traquair HRSAThe Annunciation to the Shepherds, 1900Enamel in copper mount6.5 x 9 x 6.1 cm -

Phoebe Anna Traquair HRSAHead of a Girl, around 1907Oil on canvas, laid on board34.2 x 26.5 cm

Phoebe Anna Traquair HRSAHead of a Girl, around 1907Oil on canvas, laid on board34.2 x 26.5 cm

-

-

Explore further

-

Join us for a symposium celebrating international artists

A Miscellany of Migrants: Artists and Scotland 16 January 2025 Join us for a symposium celebrating international artists and Academicians who have chosen to make Scotland their home. -

Purchase the publication

Benno Schotz and A Scots Miscellany: £10 -

View the sketchbooks

Look through Schotz digitised sketchbooks

-

Benno Schotz and A Scots Miscellany

Past viewing_room

![Benno Schotz RSA Cherna as Nefertiti, 1981 Plaster [ochred] 52 H x 27.5 W x 29 D cm](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/royalscottishacademy/images/view/c67f8b3012a9e9c7bc233a65937c517dj/royalscottishacademy-benno-schotz-rsa-cherna-as-nefertiti-1981.jpg)

![Benno Schotz RSA Figure Study Plastic metal [green patina] on wooden base 40.5 H x 16.5 W x 10 D cm](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/royalscottishacademy/images/view/a8263beafbabe807f02dcb7905d70eeej/royalscottishacademy-benno-schotz-rsa-figure-study.jpg)

![Fanindra Nath Bose ARSA Male Bust [possibly Leslie Galloway], c. 1908-26 Bronze on a marble plinth 19.8 x 7.7 x 8 cm](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/royalscottishacademy/images/view/5d10921fe2fc193c26bef9913b4884aaj/royalscottishacademy-fanindra-nath-bose-arsa-male-bust-possibly-leslie-galloway-c.-1908-26.jpg)

![Fanindra Nath Bose ARSA Sketch of Le Baiser [The Kiss] by Auguste Rodin, 1911 Pencil on paper 25 x 17.6 cm](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/royalscottishacademy/images/view/8059aba44eaa2b56dfeda4cc2dc2fce1j/royalscottishacademy-fanindra-nath-bose-arsa-sketch-of-le-baiser-the-kiss-by-auguste-rodin-1911.jpg)

![Otto Leyde (1835-1897), Prussia [now Russia]](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_620,h_620,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/ws-royalscottishacademy/usr/images/feature_panels/image/items/af/af7cd95763e946e5872a2735900d50e5/leyde-otto-rsa-no129059_crop.jpg)